Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the world. It’s so common that nearly 8 out of 10 sexually active people will be infected at some point in their lives. For most, HPV is harmless and clears on its own. But when it lingers, particularly with high-risk strains, it can trigger dangerous cellular changes that may eventually lead to cancer.

So, how does HPV actually cause cancer? Let’s walk through the process step by step.

What is HPV?

HPV is not just one virus — it’s a family of more than 200 related viruses. They infect the skin and mucous membranes, especially in the genital area, anus, mouth, and throat.

-

Low-risk HPV types (like 6 and 11): Cause warts but rarely lead to cancer.

-

High-risk HPV types (like 16, 18, 31, and 45): Cause cellular changes that can develop into cancer.

HPV spreads mainly through sexual contact, though skin-to-skin transmission is also possible. Most infections clear naturally within 1–2 years, but persistent infections with high-risk types are what set the stage for cancer.

HPV and the Body’s Defense

In a healthy person, the immune system usually recognizes and eliminates HPV before it causes trouble. However, in some cases — due to factors like a weakened immune system, smoking, poor nutrition, or simply the aggressiveness of the HPV strain — the virus persists.

Persistent infection means HPV can stay in the cells for years, subtly interfering with their normal controls. Over time, this can lead to genetic instability and eventually cancer.

The Four Steps: From HPV Infection to Cancer

Step 1: HPV Infects the Epithelial Cells

HPV enters the body through tiny abrasions in the skin or mucous membranes, often during sexual activity. Once inside, it specifically targets the basal epithelial cells, which are the deep “foundation” cells that divide to replenish skin and mucous membranes.

-

Why basal cells?

Basal cells naturally divide often, giving HPV a steady supply of host cells to replicate inside. -

What happens after infection?

The virus releases its DNA into the host cell’s nucleus and hijacks the cell’s machinery to copy itself.

At this point, the infection is usually silent — no pain, no symptoms. That’s why most people don’t even realize they have HPV. In many cases, the immune system clears it within months. But in persistent cases, HPV begins to take control of the cell’s growth mechanisms.

Step 2: HPV Oncoproteins Hijack Cell Controls

The danger of high-risk HPV lies in its oncoproteins — viral proteins that interfere with the body’s natural tumor defenses. The two most important are E6 and E7.

-

E6 Protein: Disarming p53

-

p53 is a tumor-suppressor protein, often called the “guardian of the genome.”

-

It detects DNA damage and either repairs it or triggers cell death (apoptosis) if repair isn’t possible.

-

HPV’s E6 protein binds to p53 and marks it for destruction, allowing damaged cells to survive.

-

-

E7 Protein: Disabling pRb

-

pRb (retinoblastoma protein) controls the cell cycle, preventing uncontrolled division.

-

HPV’s E7 protein inactivates pRb, removing that brake.

-

The result: infected cells multiply far more than they should.

-

By knocking out p53 and pRb, HPV essentially cuts the brakes and disables the safety airbags in the cell’s control system. This leads to uncontrolled growth and a buildup of genetic errors.

Step 3: Development of Precancerous Lesions

As abnormal cells continue dividing, they accumulate more genetic mutations. These changes are visible under a microscope as dysplasia, or precancerous lesions.

In the cervix, doctors describe these changes using cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN):

-

CIN 1 (Mild Dysplasia):

Only the lower third of the epithelium has abnormal cells. Many cases regress naturally. -

CIN 2 (Moderate Dysplasia):

About half the epithelial thickness shows abnormalities. Higher chance of progression. -

CIN 3 (Severe Dysplasia / Carcinoma in Situ):

The full thickness of the epithelium is abnormal. This is the last step before invasive cancer.

These precancerous changes can remain stable, regress, or — if unchecked — progress toward cancer. This is why regular Pap smears and HPV tests are so important: they detect precancer long before it becomes invasive.

Step 4: Invasive Cancer Development

If high-grade lesions like CIN 3 are not cleared or treated, they may progress to invasive cancer. This process involves several critical changes:

-

Breaking Through the Basement Membrane

-

Precancerous cells are confined to the epithelium.

-

When they penetrate the basement membrane, they invade deeper tissues. This marks the shift to true cancer.

-

-

Immune Evasion

-

Cancer cells develop ways to hide from immune cells.

-

They may suppress antiviral signals and create chronic inflammation, which weakens immune defense.

-

-

Unlimited Growth

-

Without p53 and pRb, cancer cells no longer obey the usual growth rules.

-

They activate telomerase, which makes them effectively “immortal.”

-

-

Angiogenesis (Blood Supply Creation)

-

Tumors send signals to grow new blood vessels.

-

This supplies nutrients and oxygen, allowing the tumor to expand.

-

-

Invasion and Metastasis

-

Cancer cells spread into nearby tissues.

-

Through blood or lymph vessels, they travel to distant organs, forming secondary tumors (metastases).

-

At this point, the disease is far more dangerous and difficult to treat — but it usually takes a decade or more to reach this stage, which is why early screening saves lives.

Which Cancers Are Caused by HPV?

HPV is linked to about 5% of all cancers worldwide. The main ones include:

-

Cervical cancer – nearly 100% of cases are HPV-related.

-

Oropharyngeal cancer – cancers of the throat, tonsils, and base of the tongue.

-

Anal cancer – strongly associated with HPV 16.

-

Vaginal and vulvar cancer – in women.

-

Penile cancer – in men.

Why Do Some HPV Infections Lead to Cancer While Others Don’t?

Most HPV infections clear without issues. Factors that increase the risk of persistence and progression include:

-

Infection with a high-risk strain (HPV 16, 18, etc.).

-

Weakened immunity (HIV, smoking, chronic illness, stress).

-

Long-term infection (lasting years instead of months).

-

Co-factors like multiple pregnancies, long-term contraceptive use, or other STIs.

How Long Does It Take for HPV to Turn Into Cancer?

The process is slow and gradual:

-

HPV infection → within months

-

Persistent infection → 2–5 years

-

Precancerous changes → 5–10 years

-

Invasive cancer → 10–20 years

This long timeline is why screening and vaccination are so effective: they catch problems early, before they become life-threatening.

Prevention: How to Stop HPV From Causing Cancer

The good news is that HPV-related cancers are largely preventable.

-

HPV Vaccination

-

Vaccines (like Gardasil 9) protect against the most dangerous HPV strains.

-

Best given before sexual activity begins, but older teens and adults can still benefit.

-

-

Regular Screening

-

Pap smears and HPV DNA testing detect early changes before cancer develops.

-

-

Healthy Lifestyle & Safe Practices

-

Avoid smoking, practice safe sex, and limit partners to reduce risk.

-

-

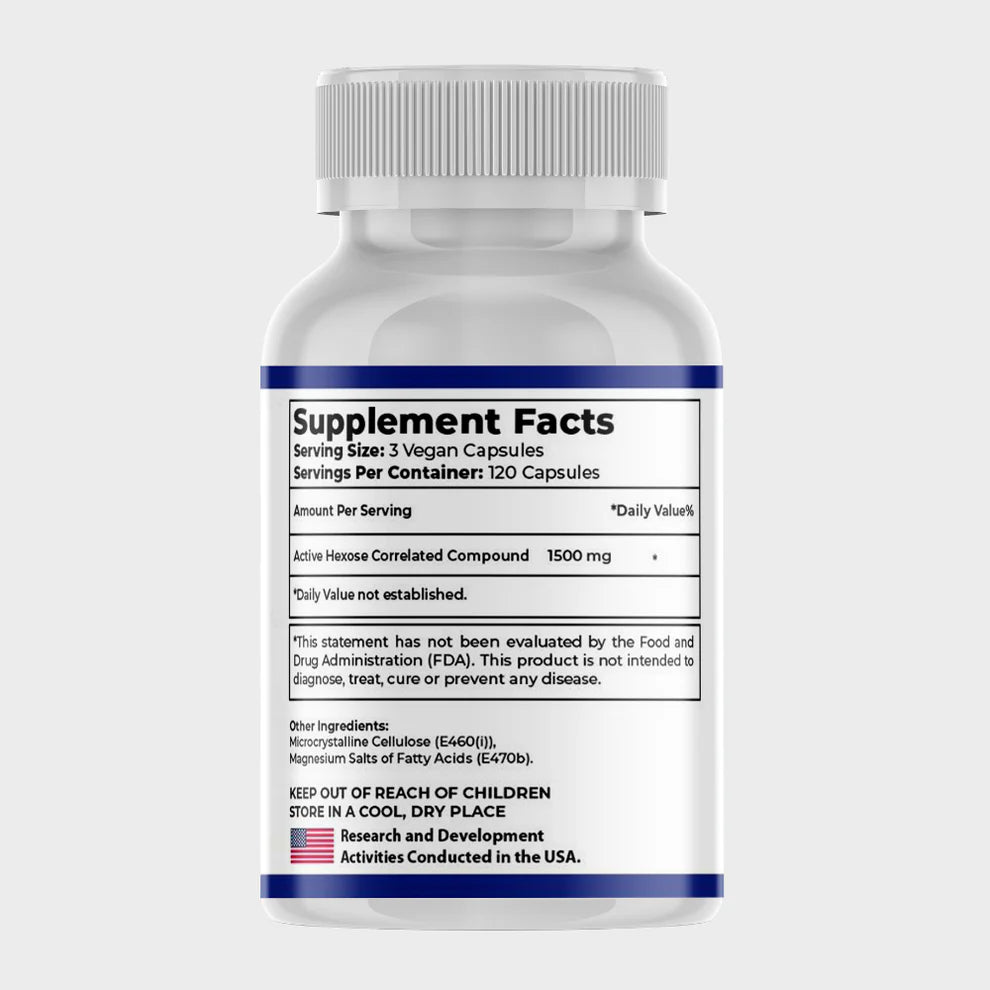

Immune Support

-

A strong immune system helps clear HPV naturally.

-

Emerging research shows Active Hexose Correlated Compound (AHCC), a mushroom extract, may support immune clearance of persistent HPV infections. Clinical studies suggest 3 grams daily could help eliminate high-risk HPV, potentially reducing cancer risk.

-

FAQs About HPV and Cancer

Does everyone with HPV get cancer?

No. Most people clear HPV naturally. Only persistent high-risk infections may lead to cancer.

How long does it take for HPV to cause cancer?

Usually 10–20 years, depending on the strain and immune response.

Can HPV cancer be treated?

Yes. Early-stage cancers are highly treatable with surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy.

Do men get HPV-related cancers?

Yes. Men can develop throat, anal, and penile cancers from HPV.

What’s the best way to protect myself?

Vaccination, regular screening, and keeping your immune system strong.

Final Takeaway

HPV causes cancer by infecting basal cells, hijacking tumor-suppressor proteins (p53 and pRb), creating precancerous lesions, and eventually breaking through tissue barriers to form invasive tumors.

The good news? With vaccines, regular screenings, and immune support, HPV-related cancers are among the most preventable cancers in the world.