Cervical cancer remains one of the most significant threats to women's health worldwide, particularly in regions with limited access to screening and healthcare services. At the heart of this disease lies a silent culprit: the Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Understanding the link between HPV and cervical cancer is crucial not only for medical professionals but for the general public as well. Education, vaccination, and early detection can make the difference between life and death.

This article delves deep into the connection between HPV and cervical cancer, the risk factors, symptoms, diagnostic methods, prevention strategies, and treatment options available.

What is HPV?

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a group of more than 200 related viruses, each designated by a number, or type. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide. It is so prevalent that most sexually active individuals will contract it at some point in their lives, often without knowing it.

HPV types are classified into low-risk and high-risk groups:

-

Low-risk HPV types, such as 6 and 11, may cause genital warts but are not associated with cancer.

-

High-risk HPV types, especially HPV 16 and 18, are responsible for the majority of HPV-related cancers, including cervical cancer.

Most HPV infections are temporary and are cleared by the immune system within one to two years. However, persistent infection with high-risk HPV can lead to cellular changes that may eventually progress to cancer.

How HPV Causes Cervical Cancer

The cervix is the lower, narrow end of the uterus that connects to the vagina. It is lined with two types of cells: squamous cells on the outer part and glandular cells on the inner part. The area where these two cell types meet is called the transformation zone, and it is particularly vulnerable to HPV infection.

When high-risk HPV infects the cells in this zone, it can integrate its DNA into the host cells. This disrupts the normal function of the cells and can lead to dysplasia—abnormal cell changes. Over time, these dysplastic cells can become precancerous and, without intervention, may develop into invasive cervical cancer.

Risk Factors for HPV and Cervical Cancer

While HPV infection is common, not everyone infected will develop cervical cancer. Several factors can increase the risk of persistent HPV infection and progression to cancer:

-

Early sexual activity: Beginning sexual activity at a young age increases the likelihood of HPV exposure.

-

Multiple sexual partners: The more partners one has, the greater the chance of encountering someone infected with HPV.

-

Weakened immune system: Conditions like HIV/AIDS or medications that suppress immunity can hinder the body’s ability to fight HPV.

-

Smoking: Tobacco use can damage cervical cells and make them more vulnerable to persistent HPV infection.

-

Long-term use of oral contraceptives: Some studies suggest that extended use of birth control pills may slightly increase cervical cancer risk.

-

Co-infection with other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs): Infections such as chlamydia or herpes can increase vulnerability.

-

Lack of regular screening: Pap smears and HPV testing can detect early cellular changes, allowing for timely treatment.

Symptoms of Cervical Cancer

In its early stages, cervical cancer often presents no symptoms, which underscores the importance of regular screening. As the disease progresses, symptoms may include:

-

Unusual vaginal bleeding (between periods, after intercourse, or postmenopause)

-

Watery or bloody vaginal discharge with a foul odor

-

Pelvic pain or pain during intercourse

-

Fatigue, weight loss, or leg pain/swelling (in advanced stages)

Screening and Diagnosis

Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers that can be effectively prevented through routine screening. There are two primary methods:

1. Pap Smear (Pap Test)

A Pap smear involves collecting cells from the cervix and examining them under a microscope for abnormalities. It can detect precancerous changes, enabling treatment before cancer develops.

2. HPV DNA Test

This test detects the presence of high-risk HPV types in cervical cells. It is often done in conjunction with a Pap smear, particularly in women over 30.

If abnormalities are found, follow-up tests such as colposcopy, biopsy, or endocervical curettage may be performed to confirm diagnosis and assess the extent of abnormal cell growth.

HPV Vaccination

Perhaps the most groundbreaking advancement in cervical cancer prevention is the development of HPV vaccines. These vaccines protect against the most common cancer-causing HPV types, particularly 16 and 18.

Approved HPV Vaccines:

-

Gardasil 9: Protects against nine HPV types (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58)

-

Gardasil: Protects against four HPV types (6, 11, 16, and 18) – no longer used in some countries

-

Cervarix: Targets HPV types 16 and 18

Vaccination Guidelines:

-

Recommended for girls and boys aged 9 to 14, ideally before sexual activity begins

-

Can be administered up to age 26, and in some cases, up to age 45

-

Given in two or three doses depending on age and health status

Vaccination does not treat existing infections or lesions, but it can prevent new infections and significantly reduce the risk of cervical and other HPV-related cancers.

Treatment of Cervical Cancer

Treatment depends on the stage of cancer, patient’s age, overall health, and desire to preserve fertility.

1. Pre-Cancerous Lesions (CIN)

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) refers to abnormal, precancerous cells on the cervix. Treatments include:

-

Cryotherapy (freezing the abnormal cells)

-

Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure (LEEP)

-

Laser therapy

-

Cold knife conization

2. Early-Stage Cervical Cancer

Treatment options may include:

-

Surgery (e.g., hysterectomy – removal of the uterus)

-

Fertility-sparing surgery (e.g., trachelectomy – removal of the cervix but not the uterus)

-

Radiation therapy

-

Chemotherapy

3. Advanced-Stage Cervical Cancer

Typically treated with a combination of:

-

Radiation and chemotherapy (chemoradiation)

-

Targeted therapy

-

Immunotherapy (e.g., pembrolizumab)

Palliative care may also be provided to manage symptoms and maintain quality of life.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

AHCC Supplement as a Complementary Approach

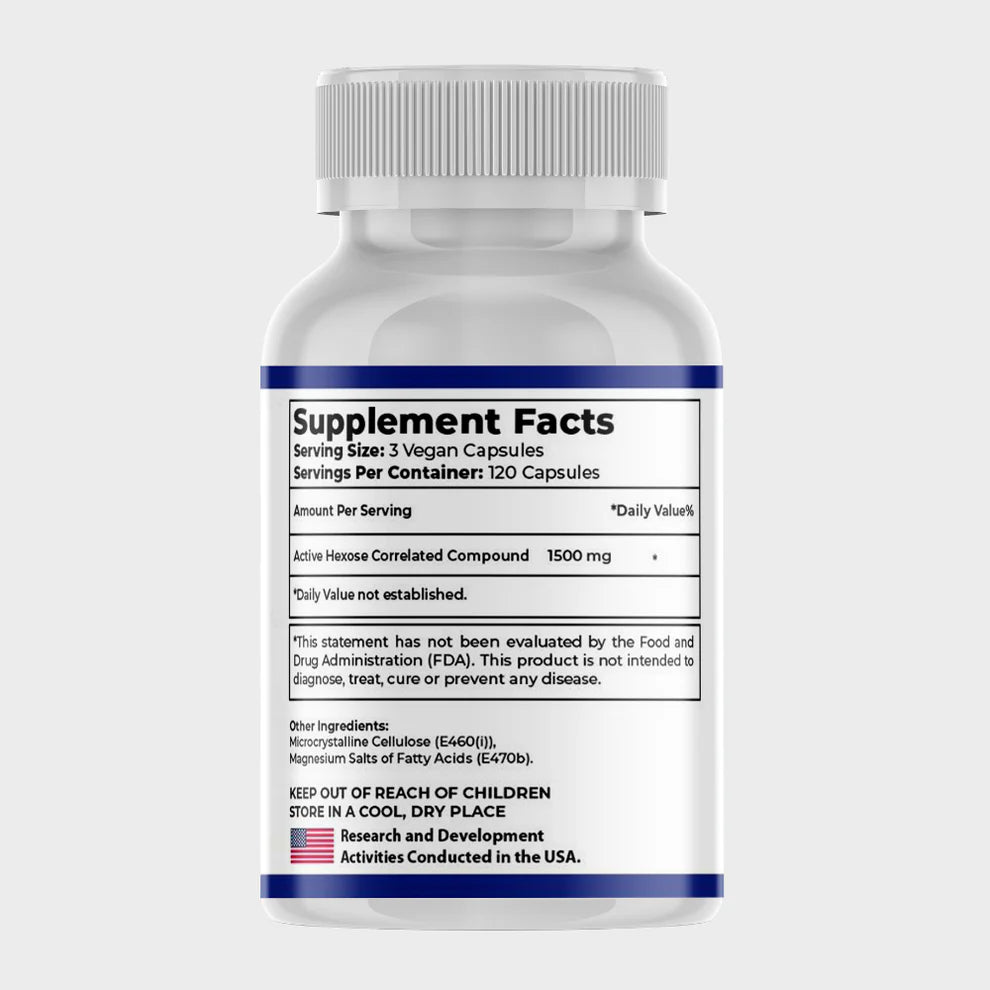

What is AHCC Supplement?

AHCC is a fermented mushroom extract rich in alpha-glucans, which are believed to enhance immune function by:

-

Stimulating natural killer (NK) cells and dendritic cells.

-

Increasing cytokine production (e.g., interferon-gamma).

-

Supporting T-cell activity, which helps the body fight infections.

AHCC and HPV Clearance

Several studies suggest that AHCC may help the immune system clear persistent HPV infections, potentially reducing the risk of cervical cancer progression:

-

A 2014 Pilot Study (University of Texas) found that AHCC supplementation (3g/day for 6 months) led to HPV clearance in 10 out of 10 women with persistent infections.

-

A 2020 Follow-Up Study reported that AHCC helped eliminate HPV in 64.7% of women after 6 months of use.

-

Proposed Mechanism: AHCC may enhance immune surveillance, helping the body recognize and eliminate HPV-infected cells.

AHCC in Cervical Cancer Support

While AHCC is not a cure for cervical cancer, it may offer benefits as an adjunctive therapy:

-

Potential to slow HPV-related dysplasia progression.

-

May improve immune response in patients undergoing chemotherapy/radiation.

-

Could reduce side effects of conventional treatments (e.g., fatigue, immunosuppression).

Current Limitations and Considerations

-

More large-scale clinical trials are needed to confirm efficacy.

-

Not a replacement for standard treatments (surgery, chemo, radiation).

-

Should be used under medical supervision, especially in immunocompromised patients.

How is AHCC Taken?

-

Typical dosage: 3 grams per day (capsules).

-

Often used for 6 months for HPV clearance.

Global Burden and Disparities

Despite being largely preventable, cervical cancer remains a major public health issue, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 90% of deaths occur. The disparity is largely due to:

-

Limited access to screening and vaccination

-

Lack of awareness and education

-

Inadequate healthcare infrastructure

In contrast, countries with robust HPV vaccination programs and screening protocols have seen a dramatic decline in cervical cancer incidence and mortality.

Psychological and Social Impact

A diagnosis of cervical cancer can be emotionally and socially devastating. Patients may face:

-

Fear, anxiety, and depression

-

Concerns about fertility and sexual function

-

Social stigma, especially in conservative societies

-

Financial burden of treatment

Support groups, counseling, and psychosocial interventions are critical for holistic patient care.

Myths and Misconceptions

There are several myths surrounding HPV and cervical cancer that need to be dispelled:

-

Myth: Only promiscuous individuals get HPV

Truth: HPV is extremely common and can affect anyone who is sexually active. -

Myth: HPV vaccination promotes early sexual activity

Truth: Studies show that vaccination does not influence sexual behavior but significantly reduces cancer risk. -

Myth: Pap smears are unnecessary after vaccination

Truth: Regular screening is still necessary, as vaccines do not cover all cancer-causing HPV types.

Prevention Strategies

Combating cervical cancer involves a multi-faceted approach:

-

HPV Vaccination: Broad immunization of both genders

-

Regular Screening: Pap smears and HPV testing as per guidelines

-

Safe Sexual Practices: Use of condoms, limiting sexual partners

-

Education and Awareness: Community outreach and school programs

-

Access to Healthcare: Strengthening primary care and follow-up services

The World Health Organization (WHO) has launched a global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem, aiming to achieve:

-

90% HPV vaccination coverage

-

70% screening coverage by age 35 and again by 45

-

90% access to treatment for precancer and cancer

Conclusion

Cervical cancer, though serious and potentially fatal, is one of the most preventable and treatable forms of cancer today. The key lies in understanding the central role of HPV, promoting vaccination, encouraging routine screening, and ensuring timely treatment.

By breaking down myths, increasing awareness, and expanding access to preventive services, the global community can move toward the elimination of cervical cancer. Each of us—patients, parents, healthcare providers, and policymakers—has a part to play in this life-saving mission.